By Verónica Pamoukaghlián

About a year ago, an editor asked me to write an analysis of the creation of myth in an audiovisual product. I decided to write about a film trailer I had just seen, which I found fascinating. This article is the result of that commission. Hope you enjoy it.

A film trailer must necessarily draw upon our own prior understanding of mythical concepts, in the Barthesian sense. By awaking in us memories of abstract ideas and familiar stereotypical characters and concepts, the authors can succeed in creating new myths associated with their films.

The semiotic exchanges at play during the watching of a film trailer are complex. The meaning of what we see  will be interpreted according to denotation but also according to the connotations of such images and sounds within our particular cultural system. Going beyond into the future, the film may succeed in creating certain myths that will become part of our cultural experience and body of language and will in turn imply new connotations for new connected images, narratives and concepts.

will be interpreted according to denotation but also according to the connotations of such images and sounds within our particular cultural system. Going beyond into the future, the film may succeed in creating certain myths that will become part of our cultural experience and body of language and will in turn imply new connotations for new connected images, narratives and concepts.

The trailer for MELANCHOLIA by Lars von Trier exudes all of these complexities, which it uses to give the object of the film an aura of intrigue and mystery. The cutting of a film trailer is by definition an attempt at the creation of a myth. The trailer represents the film, it creates an idea of it which goes beyond its actual elements, the denotation: who the actors are, who the director is, what the story seems to be about.

The first scene shown is a couple in wedding-ready attire walking through what looks like a path leading to a mansion. Expensive-looking cars are parked on one side. On the level of denotation, what we see is a woman in a white dress and tiara and a man in a tuxedo, walking. The dialogue is the following:

Woman_ Won’t even bother saying how late you are.

On a connotation level, these images evoke in us much more complex ideas. First of all, we associate this type of dress with weddings and we associate weddings on a mythical level with “happy endings” or a happy time, especially for women, if we take into account the Western narrative tradition. However, the woman’s tone and words denote anger or nervousness or both. The author is thus contradicting the myth of “weddings as happy endings,” as portrayed in popular children’s stories by the Grimm brothers and the like.

On a connotation level, these images evoke in us much more complex ideas. First of all, we associate this type of dress with weddings and we associate weddings on a mythical level with “happy endings” or a happy time, especially for women, if we take into account the Western narrative tradition. However, the woman’s tone and words denote anger or nervousness or both. The author is thus contradicting the myth of “weddings as happy endings,” as portrayed in popular children’s stories by the Grimm brothers and the like.

Moreover, on its connotation level, the setting implies that these people are rich, because of the place where they are getting married, their clothes and the cars we see by the side. The fairy-tale myth of the happy wedding is not usually complete without a promise of future wealth. In this respect, without the woman’s nervous look and words; the scene would be an ideal portrait of the “happy-ever-after” myth of fairy-tales.

In mixing the bride’s nervousness and anger with that mythical image of happiness, the director is creating a  new myth: that of the people who LOOK like they have it all to be HAPPY and yet are not. But this is not entirely a new myth; our imagination is full of memories of films and books and even stories of real people we have met or heard about who were not happy when they got married or who had it all to be happy and yet didn’t succeed at it. Therefore, there is a new level of connotation, which will build complex links in our minds between our previous knowledge and assumptions about such stories and the images before our eyes.

new myth: that of the people who LOOK like they have it all to be HAPPY and yet are not. But this is not entirely a new myth; our imagination is full of memories of films and books and even stories of real people we have met or heard about who were not happy when they got married or who had it all to be happy and yet didn’t succeed at it. Therefore, there is a new level of connotation, which will build complex links in our minds between our previous knowledge and assumptions about such stories and the images before our eyes.

Up to the 24th second, the trailer focuses on images which signify wedding celebration on a denotation level and “happy ending” and the like on a connotation level: Wedding guests dance, the bride is told that she has never been this beautiful, she says that she is thrilled, etc.

But after that, the trailer goes back to this MYTH being created, namely, that of the people who have everything to be happy on their wedding day, but are not. After we see these images of happy relatives and friends at the wedding, it is first the dialogue that reveals something amiss by referring to how much the wedding “is costing John.” This again goes to challenge the myth that was being created. Now, we learn that the wedding is “costing John a lot of money,” which implies that, at least for the character named John, this wedding has meant an economical effort, therefore the luxury we are being shown is not representative of the exact social standing of at least one of the people involved, and potentially more of them.

What we will now go on to call the MELANCHOLIA MYTH is emphasized once more with the following off-screen dialogue:

Woman_I thought you really wanted this.

Bride_But I do.

The dialogue is set against more images of “happy wedding people.” So, here is the MELANCHOLIA MYTH again: the contrast between an appearance of happiness and an inner reality of gloom and melancholy that befits the movie’s title.

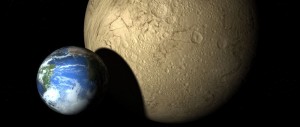

But over the next minute and a half, we will learn that the MELANCHOLIA MYTH is not only about rich people who have it all and yet cannot be happy. The melancholy expressed by the bride at many points comes to be echoed and augmented and re-signified by the powerful images of a planet that is coming closer and will imminently collide with the Earth, thus destroying the world.

But over the next minute and a half, we will learn that the MELANCHOLIA MYTH is not only about rich people who have it all and yet cannot be happy. The melancholy expressed by the bride at many points comes to be echoed and augmented and re-signified by the powerful images of a planet that is coming closer and will imminently collide with the Earth, thus destroying the world.

Now, without these images and sounds, this movie trailer’s connotations and myth creation would not be too different in our minds from the many stories, films and books we have been exposed to along our lives which present an outward idea of fairy-tale happiness to later reveal an inner uneasiness and ultimately unhappiness. But the MELANCHOLIA MYTH goes beyond that. When we get to the end of the trailer, the myth has been constructed. This is a movie about the opportunity of perfect happiness going to waste at the end of the world.

The MELANCHOLIA MYTH acquires more force because of the moment it is being released: this is 2011, when prophecies about the supposed end of the world in 2012 have been circulating for many years. On the eve of that supposed destruction, the MELANCHOLIA MYTH means something very different than it would have at a different time in history or in a different context.

To further the myth’s inner complexity and contradictions, and echoing the “not so happy fairy-tale ending” myth, the images of the planet approaching the Earth are extremely beautiful: much as the people look happy but are not, the planet approaching the Earth looks beautiful, and yet it means that the end of the world is coming and everyone will die.

In a way, the MELANCHOLIA MYTH comes to challenge the kind of bourgeois myths Roland Barthes himself claimed to despise; in this case that of the rich marrying happy couple. The scene that most directly challenges this myth is that where an older woman says, “enjoy it while it lasts; I myself hate marriages.” Much as Barthes was critical of the myth that associated wine with a good lifestyle in order to sell more bottles of it to the French public (1), the trailer is directly critical of the myth of the happy and rich marrying couple, which is in its turn, also used in advertising to sell everything from vacuum cleaners to laptop computers, all over the world.

Considering this implicit criticism of bourgeois ideals (or myths), this phrase used to describe the art of painter Camille Garcia would perfectly apply to the MELANCHOLIA trailer:

“ [it] appropriates imagery that has become synonymous with the

commodification of the fairy tale aesthetic, such as princesses, magic potions, poison

apples, and castles, which in turn evokes new significations and meanings about the

myths of today’s world through her modification of these motifs” (2)

On the other hand, Barthes saw myth-making in a negative light. He believed that myths depleted sensory experiences, such as images and words read or heard, of their meaning to create an iconic idea of them that was sometimes used to sell us on ideas and products alike.

Because the MELANCHOLIA MYTH can be seen as a meta-myth which very directly and obviously challenges those types of myths that are still so common in our day, I believe Barthes wouldn’t have been so critical of ZENTROPA’s wish to sell us the MELANCHOLIA film; just a hunch, but I guess we’ll never know the answer to that.

REFERENCES

1. Barthes, R. “Myth today.” (1957) Translated by Lavers, A. (1984) http://www.artsci.wustl.edu/~marton/myth.html (Retrieved on May 22nd, 2011)

2. De La Cruz, J. “The Art of Camille Rose Garcia: An Existential

Fairy Tale” Master’s thesis 2010, San Jose State University.

http://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4851&context=etd_theses (Retrieved on May 23rd, 2011)